India Insider: Growth Without Development an Inequality Trap

An India and Latin America Comparison

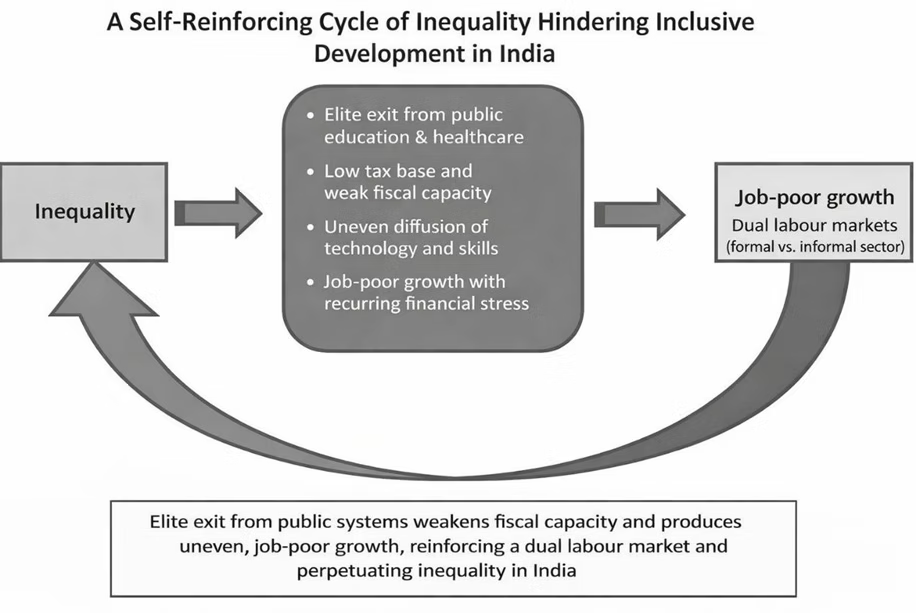

India’s strong headline growth reflects a rapid expansion of aggregate output. Yet this growth often coexists with weak job creation, uneven human capital formation, and persistent inequality. This coexistence is not a temporary anomaly. It reflects a deeper political & economic structure in which inequality itself constrains development, rather than merely emerging as a byproduct of slow growth.

This mechanism is similar to Latin America. In unequal political economies, rising income concentration encourages elites to exit from public systems like education, healthcare, transport, and social insurance. Once affluent groups no longer depend on public provision, political incentives to strengthen these systems weaken fiscal capacity erodes, public services deteriorate, and inequality becomes self-reinforcing.

Latin America’s experience illustrates this dynamic clearly. Despite periods of high growth driven by industrialization, commodity booms, or financial liberalization, many countries failed to build universal public systems. Elites relied on private schools, private healthcare, and offshore financial arrangements, while the majority depended on chronically underfunded public institutions. The result was a narrow tax base, weak state capacity, and growth that was volatile and socially shallow.

India increasingly shows signs of a similar trajectory. Public spending on health remains around 1.2 – 1.4 percent of GDP. Government expenditures on education is around 3 percent of GDP, which is low not just by OECD standards, but comparative to many middle income Latin American economies. Out of pocket healthcare costs account for roughly 45 – 50 percent of total health spending in India, among the highest shares globally. These figures point to a systematic private substitution over public provisions, a hallmark of elite exit.

Implications of Elite Leaving Public Systems

Withdrawal from public systems has direct implications for growth quality. When education and healthcare remain uneven, the diffusion of skills and productivity across the workforce is limited. Growth then concentrates in capital intensive or skill intensive enclaves, while large segments of the labor force remain trapped in low productivity informal employment. India’s employment elasticity of growth has remained structurally low, estimated at below 0.2 in recent decades, meaning that even high output growth generates relatively few jobs.

This structural weakness is reinforced by the nature of Indian capitalism. Like much of Latin America, India’s growth model rewards scale, access, and regulatory navigation more than technological risk taking. Firms that can manage land acquisition, compliance complexity, market concentration, and political connections earn higher returns than those that invest in frontier innovation. Private investment in research and development remains modest: total R&D spending in India is around 0.6 – 0.7 percent of GDP, with a particularly weak contribution from the private sector. By contrast, East Asian economies that achieved solid employment growth invested 2.0 – 4.0 percent of GDP in R&D during their catch up phases.

This outcome produces poor job growth and entrenched dual labor markets, which is also another Latin American hallmark. A relatively small formal sector benefits from capital strengthening and productivity gains, but the majority of workers remain in informal employment with stagnant wages and weak social protection. Gradually this weakens domestic demand and increases reliance on credit, exports, or asset inflation to sustain growth. Latin America’s history also shows that such growth patterns are inherently fragile.

India Vulnerability and Structural Risks

Narrow tax bases limit counter-cyclical policies. High inequality constrains mass consumption. Credit expansion often substitutes for income growth, increasing financial vulnerability. India has thus far avoided repeated balance of payments or sovereign debt crises, but the underlying structural risks look similar to Latin America. Growth looks strong on paper, yet remains vulnerable to shocks and has been slow to translate into broad based societal gains.

India differs from economies that have escaped their inequality traps, like East Asia and Northern Europe, because of poor development sequencing. These successful regional giants expanded universal public education, healthcare, and social insurance early, before inequality became politically entrenched. Elite dependence on public systems sustained fiscal capacity and productivity diffusion, allowing growth to create gainful employment.

India’s Social and Economic Dualism

India’s economic liberalization grew before consolidating universal public provisions. As growth has accelerated, inequality has widened and the exit of elites has deepened from public centers. An opportunity to create inclusive institutions during this early growth phase is missing for parts of the society.

The implication is clear. High growth alone does not guarantee development. When inequality weakens public systems and limits fiscal capacity, this discourages technological risk taking and produces inadequate job growth. Output expansion becomes narrow and periodically fragile. Latin America’s experience is a warning. Without building strong public institutions and reshaping incentives toward broad based innovation, India risks portraying impressive headline growth while vast disparity persists.

Related article of interest by Ben Ezra https://www.angrymetatraders.com/post/india-insider-the-8-2-growth-mirage-needs-a-reality-check