India Insider: Why Russian Oil Should Be Treated Skeptically

As Russian President Vladimir Putin arrives in New Delhi for a bilateral summit, the mood in India’s capital is one of profound strategic tension. The core of the problem is India’s massive appetite for discounted Russian Crude Oil, which has shielded the economy from high energy prices but is now causing significant financial and geopolitical risks. This move comes at a time when India’s most important trade surpluses lies with the West, raising anxieties about U.S sanctions and shrinking strategic space.

Trapped Rupee Problem

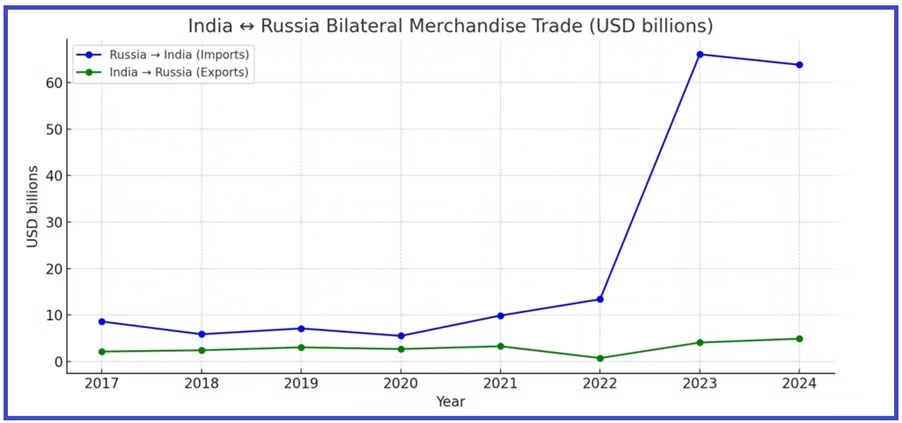

Since the Ukraine war, Russia’s share of India’s Crude Oil imports has surged from under 2% to nearly 40%. This has simultaneously inflated India’s trade deficit with Russia to nearly $59 billion.

The transactions are largely settled in Indian Rupees (INR). Moscow has accumulated billions of Rupees in Indian banks. However, because the Rupee is not fully convertible on the global market, Russia has very limited ways to use this huge surplus within India. These billions of Rupees are essentially ‘trapped liquidity’ – a problem neither country can easily solve.

The Kremlin, meanwhile, is shifting its financial allegiance. It is preparing to issue Yuan denominated sovereign bonds, a decisive step that deepens its reliance on Beijing’s financial system amid a cut off from the Western financial system. This financial trajectory clearly signals the next logical step: Russia will inevitably demand that India begin paying for its oil shipments in Chinese Yuan (CNY).

Structural Risk of Holding Chinese Yuan

India has never been comfortable holding Chinese Yuan or settling trades in the currency. That’s partly strategic as New Delhi wants to protect its geopolitical autonomy and position itself as the democratic anchor of the Global South while staying closely aligned with the West.

But Russia’s financial plumbing is now increasingly routed through China. As the Kremlin becomes more deeply integrated into China’s banking and payments system, its dependence on the Yuan becomes structural. Moscow needs Yuan not only to service Chinese creditors, but also to pay for its expanding list of manufactured imports from China. The Ruble, being a largely non-convertible currency, simply cannot support this scale of trade.

For now, Russia-China trade is balanced enough because Beijing still buys large quantities of Russian energy. But this equilibrium can shift quickly. As the Ukraine war drags on and Moscow’s defense spending rises, the Kremlin will be forced to rely even more heavily on Chinese financing, Chinese goods, and ultimately the Yuan itself, tightening its economic dependency on Beijing.

When that moment arrives, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) will be forced to accumulate Yuan as part of its Forex reserves to ensure the continued flow of oil. This decision, born of necessity, introduces a structural vulnerability into India’s financial system as the adoption of Yuan as a reserve currency subject to China’s capital controls.

Risks of Holding the Yuan

China may have both the onshore (CNY) and offshore (CNH) Yuan, but the currency is ultimately controlled by the PBOC, which makes it a risky reserve asset for India. In a crisis, Beijing’s capital controls could restrict liquidity and prevent the RBI from freely converting yuan into hard currency like the USD, effectively trapping India’s capital.

Beyond this financial rigidity, large Yuan holdings also expose India to CCP driven political risk, tying its external stability to China’s domestic decisions. And unlike the Dollar which can be deployed anywhere, Yuan reserves are usable mainly for transactions with China or countries in its financial orbit, sharply limiting India’s strategic and financial flexibility.

Strategic Win for Beijing

For Beijing, this shift delivers a double strategic win, cementing the Yuan as the dominant settlement currency across Eurasia especially among countries squeezed by Western sanctions and it allows the yuan to slip into India’s financial system indirectly, not through Chinese pressure but through Russia’s growing dependence on Chinese finance and India’s reliance on discounted Russian oil.

For Moscow, this is a reluctant compromise: giving up some monetary autonomy in exchange for necessary financial support from China.

For India, however, it introduces a new long term structural risk with a slow but steady Yuan encroachment into its trade and reserve system, operating alongside the dominant U.S Dollar. The oil corridor that was meant to offer an independent strategic opportunity for India is now becoming a channel which Beijing can strengthen its monetary footprint. In this complex triangle, India risks paying a dangerous tactical long-term price for its energy security.