India Insider: Weakening the MNREGA Employment Guarantees

When the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act was enacted in 2005, it was conceived as more than a poverty-alleviation program. It was a direct intervention in India’s rural labor market. By guaranteeing employment on demand at a statutory wage, MNREGA established what the agrarian economy had long lacked – a credible wage floor.

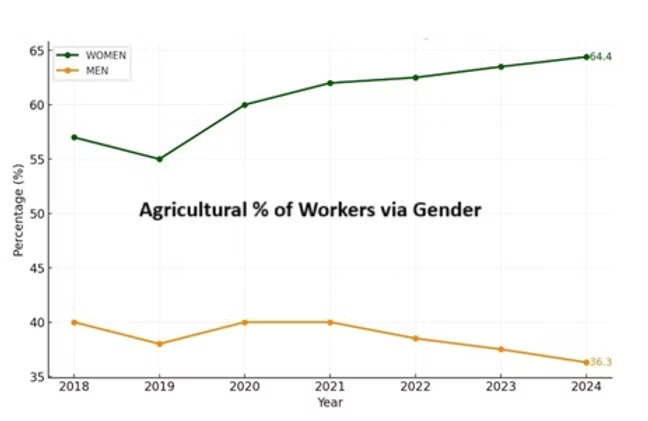

For India, where nearly half the workforce remains trapped in agriculture and align activities often involuntarily, this mattered enormously. Rural labor markets are structurally weak in India. They are seasonal, informal, and dominated by excess labor. In such conditions, wages do not rise organically. MNREGA altered that balance by providing an outside option. A worker who could demand public employment could also refuse exploitative private wages. That is why rural real wages rose meaningfully during the first decade of MNREGA’s implementation.

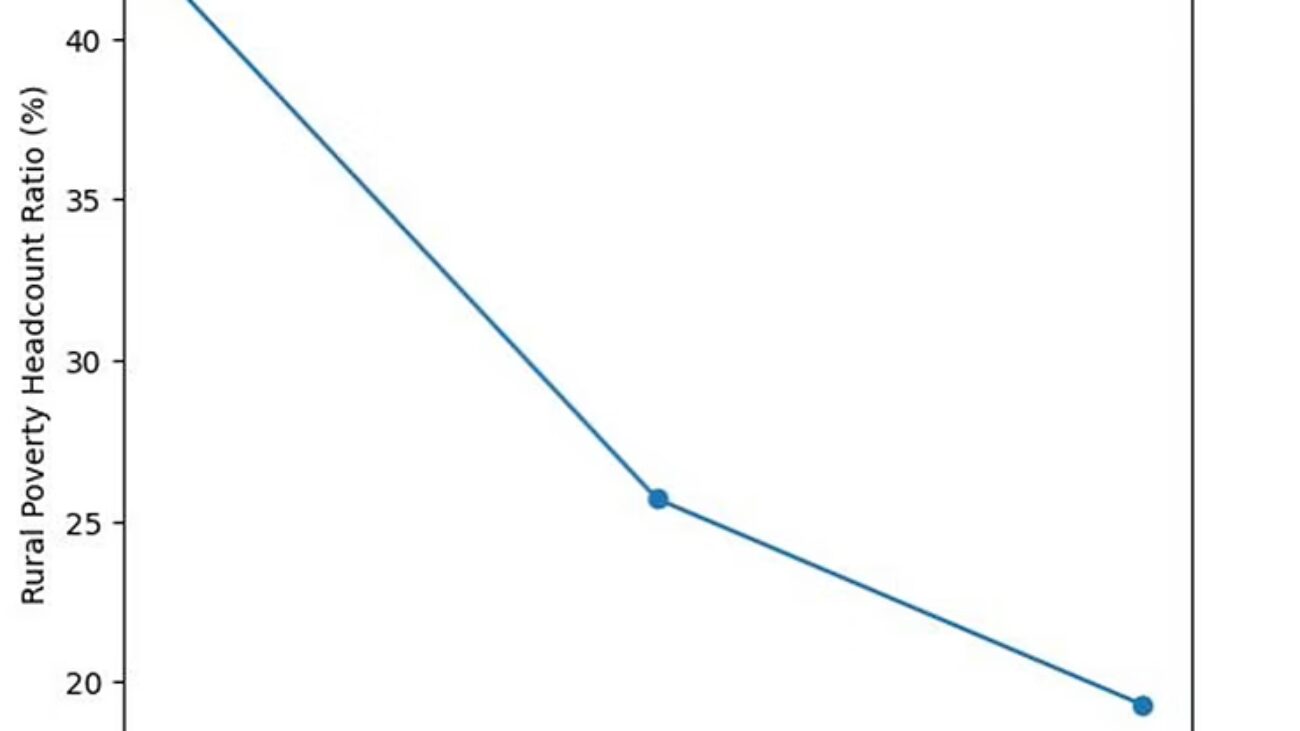

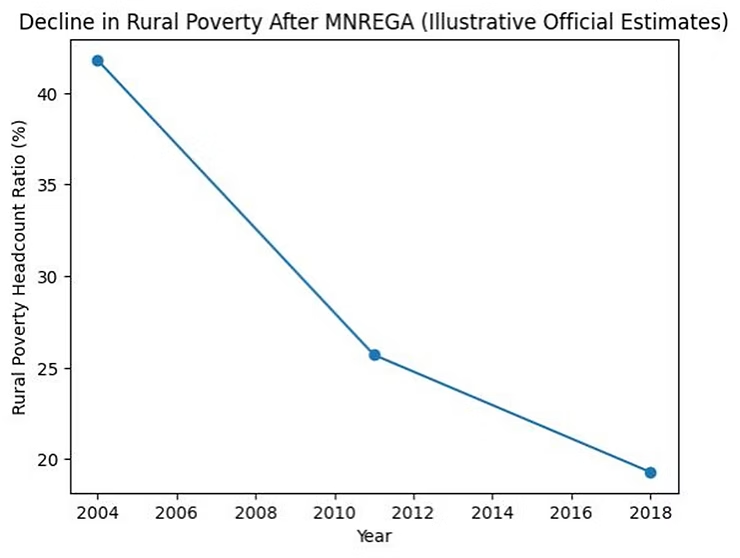

The figure above illustrates the broader context in which MNREGA operated. Rural poverty declined sharply after 2005, falling from over 40 per cent in the mid 2000s to below 20 per cent by the late 2010s. While this decline reflects multiple forces like overall growth, structural change, and social programs, micro-level studies consistently find that districts and households with higher exposure to MNREGA experienced significantly larger gains in consumption and poverty reduction compared to areas where the program was weakly implemented.

The scheme also acted as a counter cyclical stabilizer. During droughts, agrarian distress, or macro slowdowns, MNREGA expanded automatically, injecting purchasing power into rural areas. This supported consumption, reduced distress migration, and softened downturns. In macroeconomic terms, MNREGA transferred income to households with the highest marginal propensity to consume, precisely where fiscal multipliers are strongest.

Despite its strong design, MNREGA has long suffered from implementation weaknesses. Chronic delays in wage payments undermined its credibility as a reliable source of income. Corruption has generated fake muster rolls, ghost workers, inflated material bills, and substandard asset creation. Social audits which meant to be the backbone of accountability were uneven across states while effective in some.

Technological reforms such as Aadhaar linked payments, and digital attendance reduced certain leakages but introduced new problems, including worker exclusion, authentication failures, and further payment delays. The result was not only fiscal leakage, but a weakening of MNREGA’s core economic function which had promised a dependable wage floor.

Yet instead of fixing these implementation failures, a new policy chose to change the promise itself. In December 2025, this shift became explicit with the passage of the VB-G RAM G Act, 2025 in Parliament, replacing the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act with a redesigned rural jobs framework.

Under MNREGA, employment was a legal right, if work was demanded, it had to be provided. The new framework reverses this logic altogether. Employment now depends on budget limits, administrative approvals, and notifications from the center, not on demand. What was once automatic is now conditional.

This change also quietly shifts risk onto States. With limited revenue powers and tight borrowing limits, States responded by rationing work and delaying payments. As a result, the employment guarantee weakens, rural workers lose bargaining power, and wages come under pressure. What appears as fiscal control for the central government to rein on capital expenditures on paper thus becomes wage suppression in practice for rural workers.

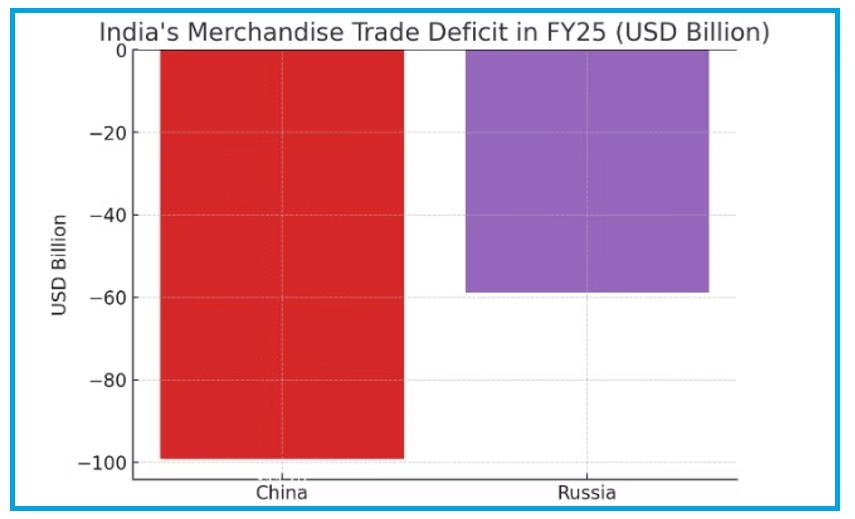

Almost half of India’s workforce, around 46 per cent, still depends on agriculture and allied rural activities for employment, even though agriculture produces a much smaller share of the country’s total output. This gap between employment and output signals very low productivity in rural work and a large pool of surplus labor. For most of these workers, moving out of agriculture is difficult. They face barriers because of a lack of skills, weak urban job absorption, high migration costs, and social constraints. As a result, the ability to bargain for higher wages is structurally limited.

In such an economy, rural labor markets tend not to be competitive. Employers often face many workers competing for few jobs, while workers have few alternative sources of income. This creates conditions close to monopsony, where employers have disproportionate power in setting wages. In the absence of an institutional counterweight, wages tend to settle near subsistence levels rather than reflecting productivity or broader economic growth.

The consequences are visible in wage outcomes. Daily wages in rural areas stagnate or decline in real terms, failing to keep pace with inflation. Over time, this suppresses labor incomes relative to profits and rents, leading to a further decline in labor’s share of national income. In effect, weakening the employment guarantee shifts income distribution away from workers and back toward employers, reinforcing existing structural inequalities in the economy.

Related article of interest by Ben Ezra https://www.angrymetatraders.com/post/india-insider-strategic-memory-and-why-unilateral-power-is-resisted