India Insider: Agriculture Still Traps Nation's Workforce

A Field Survey in South India’s Agricultural Towns

India’s growth story is usually told through noteworthy headline numbers. Yet beneath these aggregates lies a persistent imbalance, agriculture continues to employ a large share of the workforce, while contributing a much smaller share of output. This gap shapes income stability, consumption patterns, and the complicated experience of growth across much of the country for many people.

This essay uses field observations comparing two major agricultural towns in Tamil Nadu State in India, Tiruvannamalai and Kallakurichi. After analyzing their respective data and examining how this imbalance plays out on the ground, I offer my perspective.

Tiruvannamalai: Growth Without Employment Transformation

In Tiruvannamalai district, I visited several areas where housing conditions were poor and informal settlements were widespread. I have visited many households here since 2023. These conditions are now changing, but not in a way that fundamentally transforms employment.

Capital inflows from the neighboring State of Andhra Pradesh have fueled a real estate boom and expanded services such as lodging, restaurants, and transport. While this has altered the physical landscape and raised asset values, it has not created stable non-farm jobs at scale. Employment remains largely informal, seasonal, and low-paid, leaving the underlying agricultural labor trap intact.

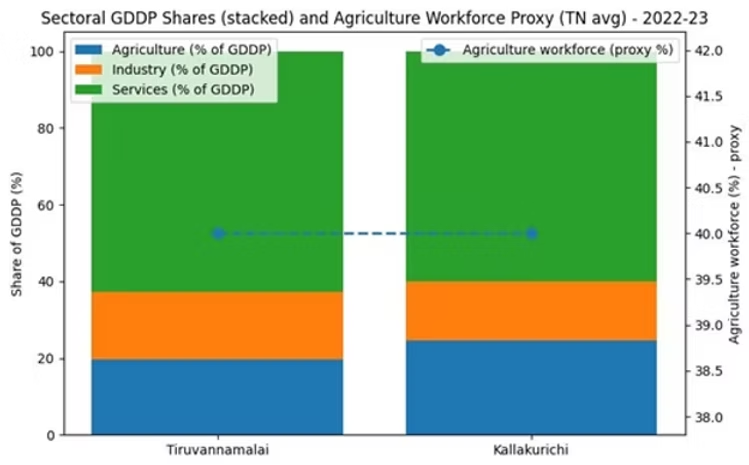

Although Tiruvannamalai exhibits a relatively high services share in district GDP, the income generated by this sector accrues from a narrow group of asset owners, intermediaries, and rent-seekers. As a result, per capita income figures overstate the extent of broad-based welfare. A large share of the workforce remains engaged in low-wage service activities with limited income security.

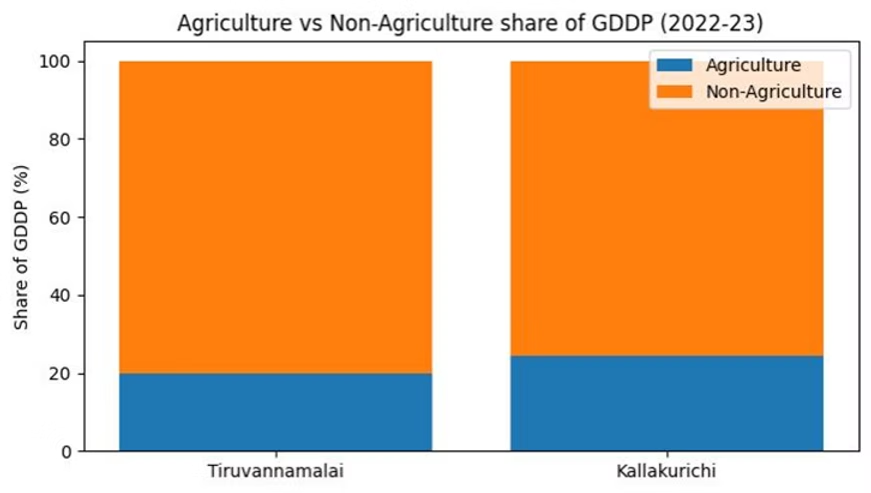

Kallakurichi: Agricultural Dependence, Weaker Services

In Kallakurichi district, the structural imbalance is even more pronounced. Agriculture accounts for a noticeably larger share of district GDP than in Tiruvannamalai, while the services share is correspondingly lower. District level GDDP and sectoral composition data from the Department of Economics and Statistics, Government of Tamil Nadu (2022–23 provisional, current prices), show that agriculture contributes roughly one-fifth of district output, even as a disproportionately large share of the workforce continues to depend on this type of work for income.

This high dependence on agriculture results in extremely low output per worker, widespread disguised unemployment, and chronically weak incomes. Growth exists, but it is concentrated in activities that do not absorb labor effectively.

Core Problem: Growth Composition, Not Growth Absence

The core structural problem in districts like Tiruvannamalai and Kallakurichi is therefore not the absence of growth, but its composition. Too many workers remain tied to a sector that generates relatively little value. Services and industry have expanded, but not in a manner that absorbs surplus rural labor at scale.

As long as labor remains trapped in low productivity farming, while non-farm sectors fail to provide stable employment opportunities, headline income measures will continue to overstate actual welfare.

Consumption Consequences of Agricultural Dependence

This imbalance has direct consequences for consumption. Towns that depend heavily on agriculture tend to exhibit weak and uneven consumption patterns. Farm incomes are inherently volatile, driven by fluctuations in commodity prices, weather conditions, and market access. In many cases, farmers are forced to sell produce at a discount, incur outright losses, or delay sales under distressing conditions. Only intermittently do they realize meaningful profits.

This volatility translates into cautious spending behavior. Consumption rises in short bursts following a good season, but thereafter contracts sharply. This pattern is clearly visible in districts such as Tiruvannamalai and Kallakurichi, where agricultural dependence suppresses steady consumption despite occasional income windfalls.

The same dynamic is visible at State level. Across Tamil Nadu, agriculture employs over 40 percent of the labor force, while contributing a far smaller share of output. The statistics exhibited at the district level are therefore not an isolated phenomenon, but a systemic one.

National Structural Imbalance

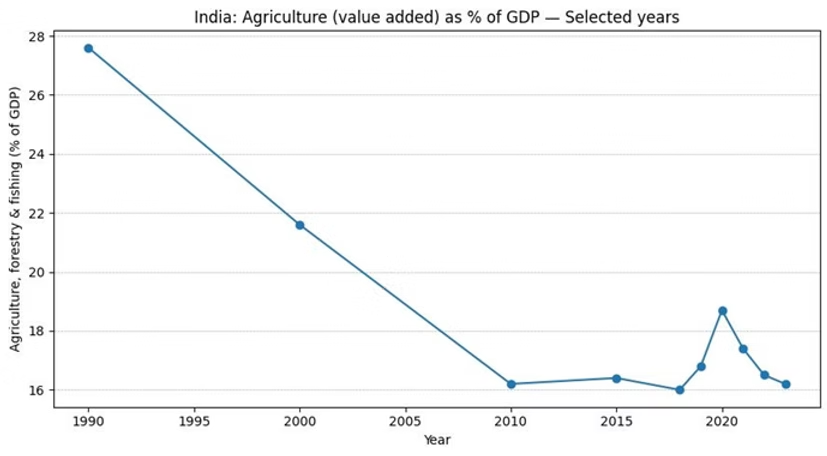

Zooming out further, what is visible in Tiruvannamalai and Kallakurichi mirrors India’s broader structural imbalance. Nationally, agriculture employs close to half the workforce, but contributes less than a fifth of GDP. This gap suppresses incomes, weakens consumption, and reflects India’s limited success in industrializing at scale.

Services have grown rapidly, but they remain reliant on capital and skill intensive, and unable to absorb surplus rural labor in large numbers. As a result, economic growth continues without broad based prosperity. Headline GDP numbers improve, but the underlying structure remains fragile.

India’s central economic scrouge is growth without labor mobility. Until workers move out of low productivity agriculture jobs and into stable non-farm employment at scale, income volatility and weak consumption will remain defining features of the economy. Regardless of how strong the headline growth numbers appear, a national challenge remains.

Related article of interest by Ben Ezra https://www.angrymetatraders.com/post/india-insider-weakening-one-of-the-largest-employment-guarantees